Jewish Ecologies: Immersive WORKSHOP in Berlin

This June 2023, Daniel Voskoboynik and I were invited to lead a parsha session and workshop for Ze Kollel (a partnership between Hillel Deutschland and Oy Vey Amsterdam) in Berlin. Parsha means ‘portion’ in Hebrew, and refers to the Jewish practice of reading a portion of the Torah each week. Daniel is an ecologist, writer and musician. These workshops built upon past collaborations with Lievnath Faber and Margot Fuentes Kratter, with whom we organized a series of workshops related to shmita (see below) over the course of four days in Barcelona, August 2022.

For the two workshops we guided, we applied ecological and sensorial pedagogies, some of which I have been developing at SOAS university.

As Daniel phrased it, we can define ecology as ‘valuing and attending to the connections that sustain life and all the lives that are moving through us, whether that be microorganisms, plants, people we meet or the air we inhale and exhale’. How we co-exist with the more-than-human world is never beyond us, ‘out there’, but forms part of our daily habits, the food we eat and the ecologies which we exist with in urban or rural environments.

In Judaism, the balance between humans, plants, animals and the land has been a concern for millennia, such as within the biblical commandment to let all agricultural land lie fallow every 7th year and renounce ownership of one’s crops. This commandment is encased within the festival ‘shmita’, meaning ‘release’ in Hebrew. We infused the questions we asked in the session with the ecological principles of shmita, explored in depth in the Palestinian Talmud. Our questions guided the group to consider human relations to the more-than-human, conceptions of land (wilderness vs. domestication) and sharing land resources with ethnic/religious groups (whether in the context of the ancient land of Canaan to the present day Israel-Palestine conflict).

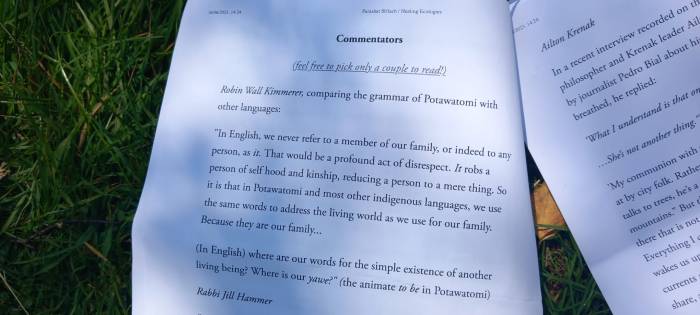

The importance of inter-cultural Torah and Talmud in a time of ecological crisis and violent occupation of shared land is essential. We drew on the teachings of many indigenous thinkers from the Americas, such as the indigenous Brazilian philosopher and activist Aílton Krenak, and Robin Wall Kimmerer, botanist and member of the Potawatomi nation.

In the second workshop we ran, Daniel was granted permission to adapt a portion of the methodology of mapeo del cuerpo-territory (body-territory mapping) to the session. This is a methodology of corporal-territorial protection and exploration elevated by the Colectivo Miradas Criticas. Through this methodology, we aimed to expand our literacy when it comes to mapping the inter-connected dynamics between the body, the self and the landscapes around us.

Finally, we aimed to encourage a more ecological approach to reading and analyzing the Torah/Talmud**. In Judaism, the traditional mode of textual study between two people (or, a ‘chevrusa’, which means friendship in Aramaic) often relies on conversation, usually following a close reading of the text and taking place inside (such as in a Yeshiva). During the chevrusa session, we invited the group to walk around outside in silence, sensorial engaging with the plants and elements in the garden. How might these beings feel their way through space, experience stress or safety where they are? These encounters highlight the limits of human language (and even text) when thinking through phenomena in a deeply ecological/ empathetic mode.

Some of the themes our participants brought up in the group discussions during the session included:

> The (im)possibilities of being able to perceive the world from a non-human perspective

> The way language (such as grammar) and also textual practises can shape relations to the more than human world

> How we relate to areas of land such as ‘wilderness’ and its representation in the Torah/ Talmud

> Hierarchies of species as represented in Jewish written/oral Torah

Ecological pedagogies encourage individuals to place themselves, in both an affective, sensory and discursive way, within the wider context of the ecosystem (allowing that the scientific language of ‘ecosystem’ does not reflect the plethora of how humans conceive of the wider environment). Feeling and encountering the interconnection between multiple beings may make this material reality more immediate than text based or more abstract encounters. These pedagogies can be applied to Jewish textual practices as much as to other cultural/religious contexts. My anthropological learning also shapes this approach, where ‘making the familiar strange and the strange familiar’ enables us to question semi-conscious, assumed ‘truths’ about the world through making us become aware of our deeply held beliefs or ontologies (sense of what is ‘real’/exists in the world) in a self-reflexive manner, such as the meaning of ‘human’. I have also tried to bring sensorial, outdoors learning into SOAS anthropology department by exploring multi-species ethnographic research methodologies in a non-linguistic, sensory setting, preparing students for multi-species encounters ‘in the field’.

*my framing of Zionism in this document does not represent the views of all those in the session, nor Ze Kollel, Hillel Deutschland or Oy Vey Amsterdam.

**It should be noted that textual study is not the primary or only way in which Jews have or do explore questions about ‘ecology’. There is an exciting movement of (often radical diasporist) Jewish farmers in the States and Europe, applying principles from the texts to their farming practices. Many thinkers within diasporic ‘earth based Judaism’ movements also centralize the (at times sidelined) agro-ecological aspects of the religion, applying them to diasporic settings, such as Miknaf Haaretz. Lastly, we are not stating that Jewish textual study in more traditional forms is within itself ‘un-ecological’, while we are aware that definitions of ‘text’ and ‘language’ are relative.

***cover photo taken by Daniel in a forest close to Wannsee Lake, Germany.