Culture Cuts: Sri Lankan Tamils

*All names have been changed, and photos obscured, to secure the subjects’ anonymity. There are no facial photos of the interviewees. Place names and specific information are included to the degree that the interviewee was comfortable with..

.

Published by Novara Media

.

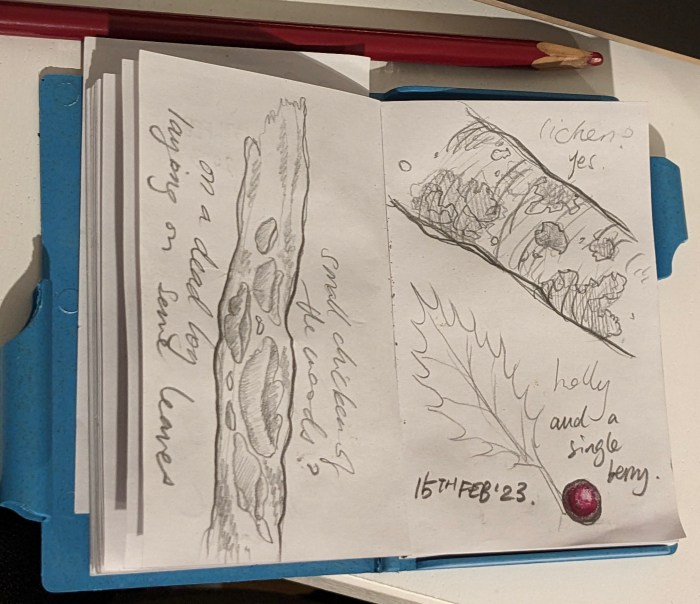

“I want to show you a cemetery”, an unexpected endnote to an interview about teaching the Tamil language in the borough of Newham. Lashani pushes open the door of a disused room, three flights up. Light enters from a window yawning over a communal space, encased by a block of houses. Our viewpoint is through the back of the London Tamil Sangam of which Lashani is the head teacher.

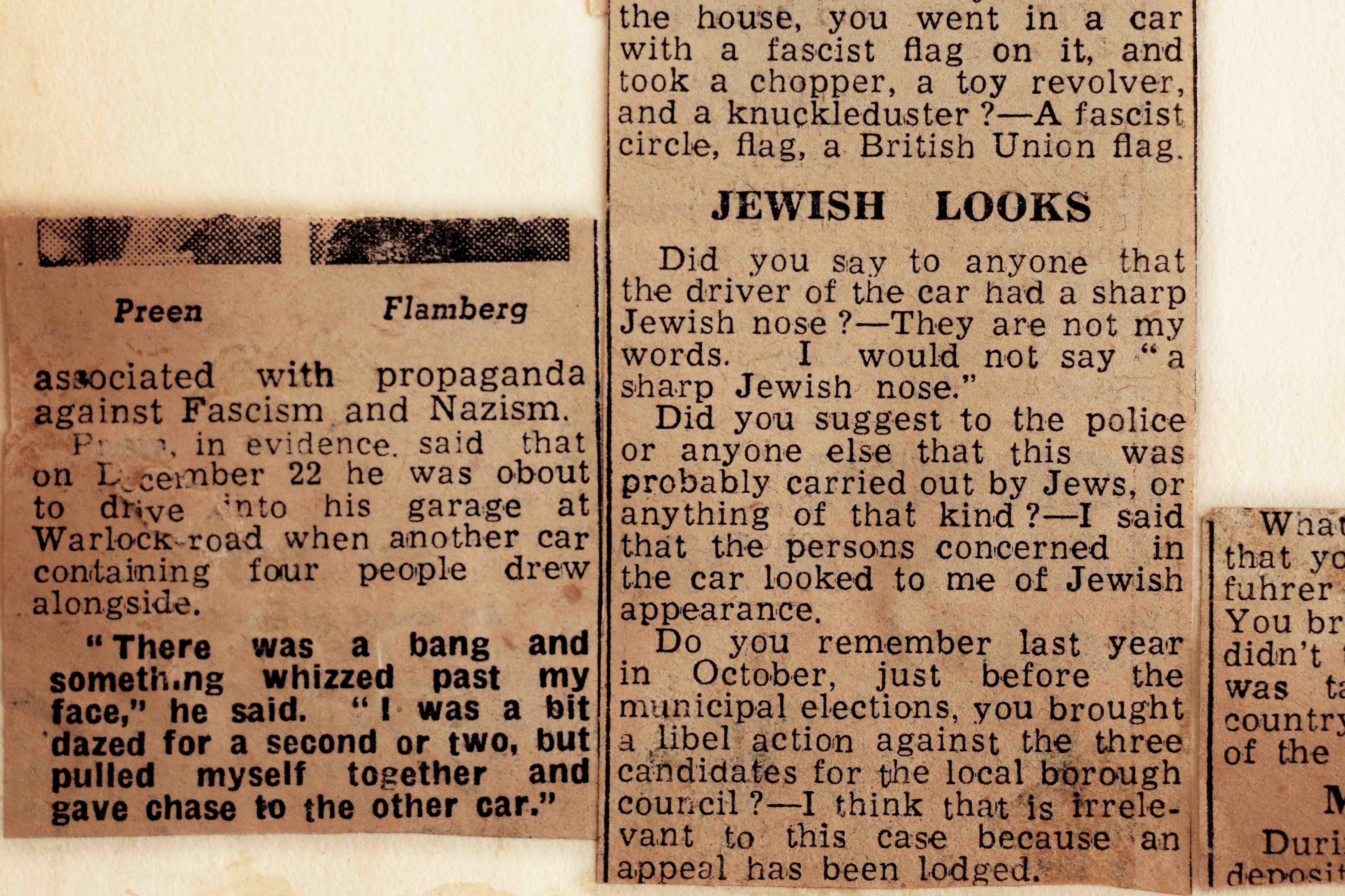

“Its a disused Jewish cemetery from before the 2nd world war, you can only see it from these houses,” Lashani tells me. She points to the dignified epitaphs and faded Hebrew script. The cemetery’s gates have been closed to the public since 2003, after 386 of its tombstones were defaced. Their crumbling facades recall the bombs that swept across London.

.

.

. The Sangam center, founded in 1936, is one of the oldest Tamil organisations in London.

.

The centre teaches the Tamil language to second-generation Sri Lankan Tamil refugees, many of which are Newham residents. A small proportion of Lashini’s student’s parents came to the UK during the course of Sri Lanka’s 26 year civil war. The economic reasons for immigration in the 70’s became the seeking of asylum in the 80’s following the country’s growing instability.

Today, there are close to 200,000 Sri Lankan Tamils in England, with the majority living in London.

Although Sri Lankan Tamils have found employment in financial and medical fields since the 70s, many refugee and asylum seekers from Sri Lanka seek emotional and practical support from community centres. Offering financial advice, legal aid, free meals, English lessons and counselling, these centres are fuelled by donations, volunteers and council grant schemes.

However, councils across London are drastically reducing their funding to the centres that support this diasporic group, despite growing demands for their services under the last five years of the Conservative’s austerity measures. In London’s most deprived communities, social care has fallen by £65 per head since 2010, while charities have lost over £3.8 bn from Government funding over the last decade.

Before travelling to Newham to find out about how local government cuts are affecting London’s Tamil community, I went to Murugan Temple in Highgate to learn about Sri Lanka’s past.

26 Years of Civil War

Bali sighs. This conversation is at best recycled. New revelations are not unearthed. He treads with expert feet along the timeline of Sri Lanka’s past violence. He is a Tamil, and left Sri Lanka in 1976 following the country’s civil unrest.

Nearing his 80’s, he tends to circumvent political discussion, volunteering every weekend at Highgate’s Murugan Temple. “As long as your heart is clear you can come to this temple. We ingrain no politics – God can punish those who are bad, that is my philosophy.”

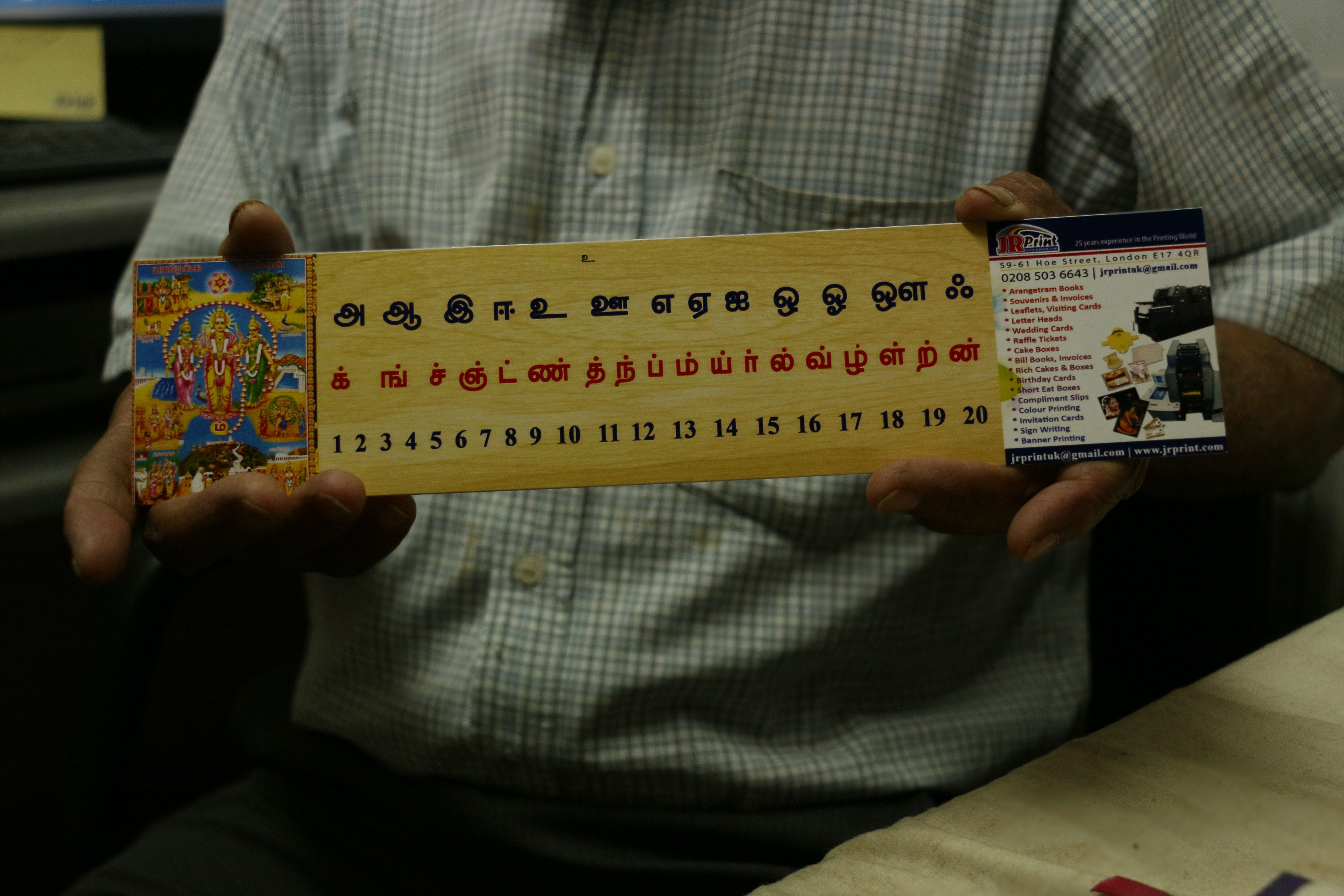

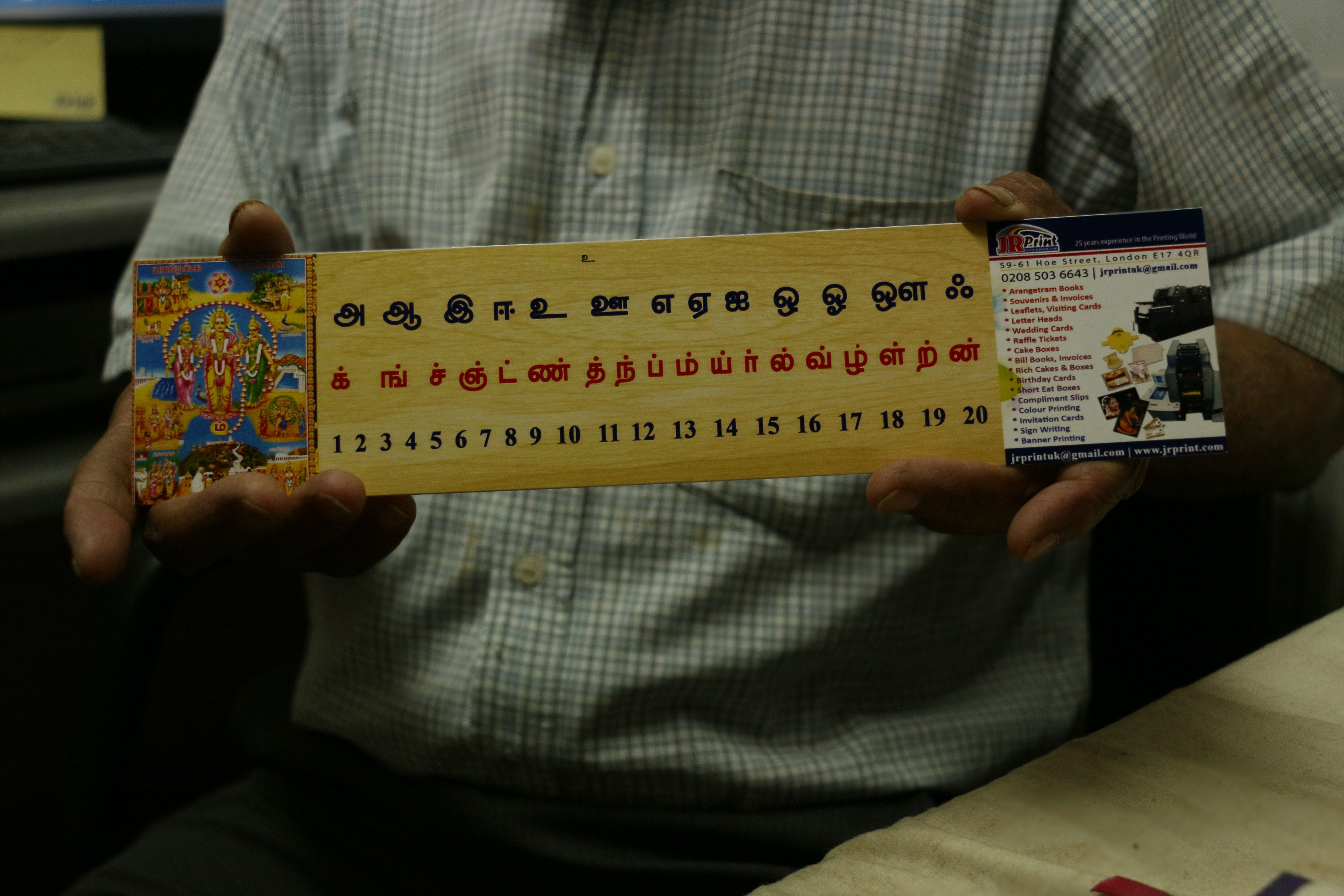

We walk along the 12 inward facing shrines of the temple’s body. Worshipers perform parikrama: making circles around the statues of Gods. “We bought the deities over from Southern India”, he whispers, not to disturb the Sanskrit chants emerging from the temple’s inner sanctum. He ushers me to the ticket office, our conversation interrupted when he gives me a placard displaying the Tamil alphabet.

.

.

The Tamil language is spoken from Southern India to Malaysia, and by Tamil diasporic communities across the globe. Online forums contest whether the language is older than Sanskrit.

.

.

In 1948, Britain’s colonial rule of Sri Lanka ended. During their regime, ethnic tensions between the Sinhalese and Tamil population emerged, exacerbated by Britain’s unfair advantaging of the Tamil minority. The Sinhalese, mainly Buddhist and Sinhala speaking, make up roughly 75% of Sri Lanka’s population, while the Tamils, mainly Hindu and Tamil speaking, make up just under 12%.

“The Tamils were in the top posts during Britain’s rule. When the Sinhalese came into power following Independence, they wanted to stop the Tamils from going to university”, explains Bali.

Over the course of the following few decades, a series of reforms were implemented by the Sinhalese to disadvantage the Tamils, beginning with education. “The Tamil’s entrance marks were made higher than theirs, making it very difficult for them to get into higher education”. In 1956, Sinhalese was made the country’s only official language.

After nearly three decades of Tamil oppression under Sinhalese rule, 1976 saw the formation of the Tamil Tigers. Prabakaran, who led and founded the military group, became the unfiltered microphone that amplified thousands of disillusioned Tamil voices. The group’s main objective was to secure a separatist state for the Tamils, within Sri Lanka’s borders.

A few months following the Tiger’s formation, The Tamil United Liberation Front, a Pro-Tamil rights parties, entered their first general election. Bali started to cry as he told me about the democratic party, holding its biography. With 70% of the electorate being Sinhalese, the party stood little chance of instigating reforms.

With the chances of peaceful political reform for the Tamils minimal, the Tigers became the vanguards of Independence. They attacked both Sinhalese and Tamils to secure this title. Freedom fighters quickly morphed into terrorists on the international podium.

“They slipped a letter warning that they would kill my father if he remained in Northern Sri Lanka in 1985. He was a District Chairman for the government. While he was sleeping, they came and shot him in the head. They didn’t have a plan, they just shot”.

.

.

.Hindu Priests are traditionally Brahmins, the highest caste within the Hindu System. The Tamil Tigers fought to dissolve the caste system, advocating for an egalitarian and Communistic mode of governance.

.

.The main duty of the Pujari is to act as an intermediate between the worshiper and God. They traditionally wear a Janaeu, or white thread around the body. The knot symbolises the priests’ pledge to to be pious.

.

The Tigers’ Separatist nation was gradually secured in the North and East of the country, with its own functioning government, bank and television station.

The perfecting of the suicide bomber. Massacres of Sinhalese Civilians. The utilisation of child soldiers. The murder of Tamil defectors. It was not easy for the Tiger’s to retain the core ideals of their manifesto while preventing the government’s forces from defeating their de facto state.

Sri Lanka’s majority-Sinhalese military were guilty of numerous human right’s abuses during their combat with the Tigers. Notorious for their high levels of sexual assault of woman civilians and Tiger fighters, this problem has far from disappeared. During the war, thousands of Tamil civilians disappeared. White vans would remove suspected Tiger sympathisers to faceless detention centres.

The civil war clawed itself into the 21st century. The fighting picked up speed, and international recognition, until its culmination in 2009. In the last year of fighting, the accusatory fingers of foreign governments pointed at Rajapaksa, Sri Lanka’s former president:

During the defeat of the Tamil Tiger’s in 2009, thousands of Tamil civilians were shelled in “safe zones”. These zones had been allocated by the Sri Lankan government in the final phase of the war. The casualties proliferated on both sides. Up to 20,000 Sinhalese and Tamils were killed in the last 4 months of combat.

Ethnic cleansing! Genocide! Protests in Parliament Square surged. Calls for foreign intervention were unanswered. The final surrender of the Tigers came a day before Prabakaran’s body was found floating in mangroves.

Today, Sri Lanka’s recovery from the war is slow. Improvements of Tamil rights under the new president Sirisena lack momentum. Military camps and detentions centres are still rooted on Northern Sri Lanka’s soil. War crime allegations have not been assessed by an external judiciary. The newly elected army chief lead a key division of the military during the last two months of the war.

.

.

The Temple’s priests, or pujaris, conduct the daily puja, a Sanskrit word for worship. There are up to 16 main steps in the worship, from washing the deity’s feet to offering them a seat.

.

Bali traces invisible lines over his open palm. At the end of our conversation, he returns to the 80s:

“They burnt our library in Jaffna in 1981. There were Tamil scriptures, manuscripts. They were written on Palmera leaves – they are all gone..the whole collection was kept in the library”. Jaffna library was burnt during civilian riots. A similar dent was felt in the cultural archives of Mao’s China and Nazi Germany – the burning of books always ignites a greater fire.

.

.

The Tamil Language – Culture Cuts

.

.

Bali’s regret of the offensive against Tamil cultural artefacts, reverberates in Selvan’s concerns about the state of the Tamil culture under the current Sri Lankan government. I met Selvan, a Tamil refugee of the 80’s, in a Hare Krishna temple in East Croyden.

He promotes the teaching of the Tamil language in London, fuelled through his fears of its increasingly marginalised status in Sri Lanka. FreedomHouse reports that ‘the status of Sinhala as the official language puts Tamils and other non-Sinhala speakers at a disadvantage’.

Sinhala is spoken predominantly in the South, the region with the most economic growth and governmental departments, while the North, with high levels of poverty and unemployment, is majority Tamil speaking.

In the North today, efforts to improve an economy failing through the infrastructural damages of the war are minimal. Sirisena’s lack of initiative is felt by Selvan: The school of his Tamil-majority village was bombed 7 years ago. Today, the rubble has been cleared, but there are no efforts to reconstruct the building.

.

.

After negotiating with locals MPs and gaining approval from the region’s military commander, Selvan’s charity, Sinnathurai Children Foundation was registered. “We built the old school again and now it’s an afternoon school for children. When it rains they are living in huts still!” (pictured above).

.

.

Selvan sees London’s community centres as crucial for fostering Tamil culture outside of Sri Lanka’s borders. “We are distributed everywhere now, all over the world. We have to show our children what our culture is, our religion – to teach them the language…A lot of things have been lost but even if we move to another country we still have our culture”.

However, Lashani, from the London Tamil Sangam, has had to start charging a small fee for lessons following local government cuts.

Lashani prepares her students for the Tamil language GCSE, enabling many 2nd generation refugees to speak to family members in Sri Lankan that do not speak English.

.

.

The Sangam centre’s library houses current Sri Lankan and Southern Indian Tamil newspapers, as well as poems originating from 300 BCE.

.

.

“Many of the elder generation are lonely and can only speak Tamil here,” Lashani explains. “People are suffering in silence.. I lost my husband a couple of months ago..I can share my sorrow with people, and speak about them in my own language”. With a further £20m cuts this year to resources teaching the English language, the center works to prevent language barriers from isolating refugees.

The cuts faced by the Sangam center are marginal in comparison to the nearby Upton and Hartley centres. Following a withdrawal of fundings from NewHam’s shrinking grant scheme, both centres closed last year. The charities hosted lessons in Hindu culture, English classes and events for the elderly.

Newham council, despite being the 6 most deprived area in England, will receive £284 less for every home in the borough as of 2017, while Richmond, a substantially wealthier area, will have its grants cuts by just £57 per home.

The effects of these cuts reverberate in North London, with New Barnet’s Sangam Centre’s facing depleting council funds, a charity providing advice to Sri Lankan Tamil women. With charity grants predicted to have disappeared by the next 4 years, this decline in funding can only sharpen.

.

.

London’s Community spaces – Frontiers to Censorship

.

.

“The Tigers are freedom fighters”, Ravi asserts. ‘Ravi’, a fake name, agreed to talk to me after I assured him that the interview would be anonymous. Community spaces encourage the sharing of sorrow, the dispersion of loneliness. They also become places where frustration can be shared without fear of censorship.

Ravi taps his hand on his knee. His gold chains vibrate with the movement. The emblems are obscured as they disappear into his white t-shirt. We sit on a soft carpet in a temple in Wembley. He is a second-generation refugee. “I know nothing, only what my Mum tells me”. His proviso dissolves as we begin talking about censorship in Sri Lanka.

“I have friends here with bullet wounds, I can give you their number”. The offer was never followed up. What’s in it for him? To publicly discuss or protest for Tamil rights in London could place yourself on Sri Lanka’s watch list:

Under Sri Lanka’s Prevention of Terrorism Act, suspected Tiger sympathisers are detained on return to the capital’s airport. This can result in interrogation and torture without trial.

“If you put my name or my picture in a magazine, then I can’t go back to Sri Lanka..I protested in 2009 during the civil war, there were photos of me in Parliament Square – there’s a 50/50 chance I’ll be caught if I went back”.

.

.

“It is not a catch-penny book, with life like that of a mushroom”. An excerpt from the Preface of the Bhavitha Gita, the main text of the Hindu and Hare Krishna faith.

.

.

The Home Office’s August Report on Sri Lanka disclosed that family members have been questioned in Sri Lanka, following the participation of relatives in anti-government protests abroad.

Ravi has family in Sri Lanka. For many in the same position, it is fear for their protection that dictates how politically active they are in their places of asylum, meaning community centres and temples often become substitutions for street protests.

Wembley’s Hindu temples will have to shoulder increasing council tax following Brent’s growing cuts, despite the fact that many of them relieve the pressure of food banks by providing free meals on a daily basis. The council recognises this financial reality as a pattern spanning across the UK’s borroughs: ‘We are not alone, as around 86 per cent of councils are planning to increase council tax’, their website states.

.

.

The UK’s Closing Borders

.

.

Beyond the shrinking resources that help the Sri Lankan’s who have been granted asylum in the UK, it is also the routes for potential refugees that are threatened under the UK’s tightening borders.

Newham’s Tamil Welfare Association has been supporting asylum seekers coming to the UK from Sri Lanka since 1985. The center is a 10 minute walk from the Sangam Tamil Language School. Along High Street North, connecting the two centres, the walk of Hindus to their daily puja (worship) is soundtracked by the sound of saluhs (prayers) in the borough’s local mosques.

.

.

.

.

The centre’s building is small, its outreach extensive: Asylum seekers with no legal representation and stuck in detention centres while their claim is reviewed, or refugees seeking legal advice, often call Pradeep, one of the founders.

A woman in her 50’s cries in the centre’s waiting room, she is handed a letter by one of the volunteers. I question whether I should be there, taking up an hour of Pradeep’s time. The center has about 30 walk-ins a day. During our interview, he would run to retrieve a yellow legal file and deposit it on the desk of his colleagues, talking on the phone in Tamil.

The UK’s toughening asylum seeking process highlights the importance of the center. Since 2005, the majority of refugees are granted access to the UK for only 5 years, while over a half of asylum seekers are detained during their application review.

Pradeep knows the UK’s border control process intimately – he was part of the surge of Tamil refugees seeking asylum in England in the 1980’s during the build-up to the civil war.

He’s laughing. Pradeep’s response to my question of whether he thought conditions for asylum seekers had improved significantly since his arrival, which he recounts to me:

“I left on my own. Afterwards my family came here, one by one. Actually my father was shot by the Sinhalese and he survived. When I arrived here, I was detained with 58 other Tamils in the Ashford Remand center in 1985, but we started to fight. With the help of Jeremy Corbyn, the detainees were released. We initially formed this organisation as a self-help group, with a group of refugees putting money in”.

Pradeep is not overawed with Jacques Audiard’s recent film Dheepan, depicting the struggles of a Tamil refugee following his arrival in Europe. The film ends with an angelic choir. They infuse a shot of Dheepan, the protagonist, as a black-cab driver parking in his suburban driveway.

He see’s the blockbuster as symptomatic of a lack of understanding surrounding the reality facing many refugees on arrival to their places of asylum. Perhaps the recent Ken Loach film I am Daniel Blake, with its benefit freezes and food banks, is a more accurate depiction of life following the granting of refugee status.

The UK’s shrinking support for incoming asylum seekers and refugees, renders the future of Pradeep’s charity unstable. Despite the centre’s popularity, it increasingly relies on volunteers, and donations from local residents.

After its near collapse in 1994 following a withdrawal of government funding, its continuation is testament to the associations’s importance in alleviating the suffering of the Sri Lankan Tamil refugee, and asylum seekers, that reach out to it from across the UK. However, Pradeep, remains concerned for his centre’s future:

“There is bad media coverage of the situation and funders are withdrawing. Policy wise the government is not giving grants for asylum seekers.. the general public is a bit scared of refugees. It’s very hard to run a refugee charity..normal charities don’t face hatred”.

.

.

.

.

Refugee centres provided advice to Sri Lankan Tamils in South-East London are also facing cuts. An employee from Lewisham’s Refugee and Migrant Network reports that ‘our charity has had to absorb the clients affected by centres that have closed down due to funding cuts’.

These centres, supporting London’s multiple diasporic communities, have experienced increasing demand: the Red Cross reports that over 3,000 asylum seekers have been living in ‘destitution’ this year.

After an asylum seeker is granted refugee status, the government grants them 28 days before their financial support is cut, despite the fact that finding a job often extends far beyond a month. As a direct result of this law, the Red Cross measured a 10% rise in refugees seeking food parcels or emergency cash from them since 2015.

Autumn Statement

.

.

In 2013, David Cameron broke official protocol by visiting a camp for displaced Tamils in Northern Sri Lanka. His cameo appearance intending to draw attention to Sri Lanka’s lack of investigation into alleged war crimes. Cameron left, the news moved on but the cutting of resources that support Sri Lankan refugees in the UK continued.

Cameron’s stunt echoes Theresa May’s first series of speeches as Prime Minister, broadcasting solidarity with the ‘working’ families of England. Encouraging words, often unsubstantiated.

Change, however, is forthcoming in the Home Office. As of 2016, only 14 out of 147 asylum applications were accepted from Sri Lanka. This is a distinct fall from 2015’s 45% acceptance rate of appeals.

The decrease in asylum granting is not so much a reaction to some of the ‘improvements’ marked in Sri Lanka, but to the influx of refugees to European and UK borders. With the UK gaining more control over its borders in the wake of Brexit, this decrease is set to continue.

The futures’ of Sri Lankan Tamils with rejected asylum applications are unstable – they are sent back to a country they initially left over concerns for their safety. Jasmine Pilbrow, a student who refused to sit down on a flight instrumental in the deportation of a Sri Lankan Tamil in Melbourne last year, draws media attention to a process seldom reported on.

The ongoing problems in Sri Lanka should make the obstacles faced by Tamils refugees harder to ignore: the censors on freedom of speech, the difficulty of Tamils resettling in the North following their removal during the war and the threat of torture and detention are proving slow to improve.

Once asylum seekers arrive to the UK’s borders, the support of these community centres are crucial. Many asylum seekers’ visa applications are stretched from months to years, with the UK having the longest wait for a work permit in Europe. With social welfare continuously decreasing, the practical and emotional support of these centres for Sri Lankan Tamil Refugees grow in importance.

The livelihoods of these centres will be measured in Phillip Hammond’s upcoming autumn statement. As it stands, the UK’s austerity measures are set to continue into the 2020s, although Hammond has hinted at a divergence from Osborne’s long-term budget. However, the new Chancellor’s recent assurance that ‘we remain committed to fiscal discipline’ renders any substantial reversal of the Conservative’s ongoing cuts doubtful.

A Catalan Independence march last November, by Barcelona’s Placa Espana.

A Catalan Independence march last November, by Barcelona’s Placa Espana. A Catalan Independence march last November, by Barcelona’s Placa Espana.

A Catalan Independence march last November, by Barcelona’s Placa Espana. A Spanish patriot in Barcelona on the 12th of October, The National Day of Spain.

A Spanish patriot in Barcelona on the 12th of October, The National Day of Spain. A political pero in Barcelona on the 12th of October, The National Day of Spain (Pro-Spanish unity march)

A political pero in Barcelona on the 12th of October, The National Day of Spain (Pro-Spanish unity march) A Catalan Independence march last November, by Barcelona’s Placa Espana.

A Catalan Independence march last November, by Barcelona’s Placa Espana. A Spanish patriot in Barcelona on the 12th of October, The National Day of Spain.

A Spanish patriot in Barcelona on the 12th of October, The National Day of Spain. A Catalan Independence march last November, by Barcelona’s Placa Espana.

A Catalan Independence march last November, by Barcelona’s Placa Espana.