The Unsung Savior of Cairo’s Jewish Community

Posted on July 21, 2019

commissioned by Haaretz

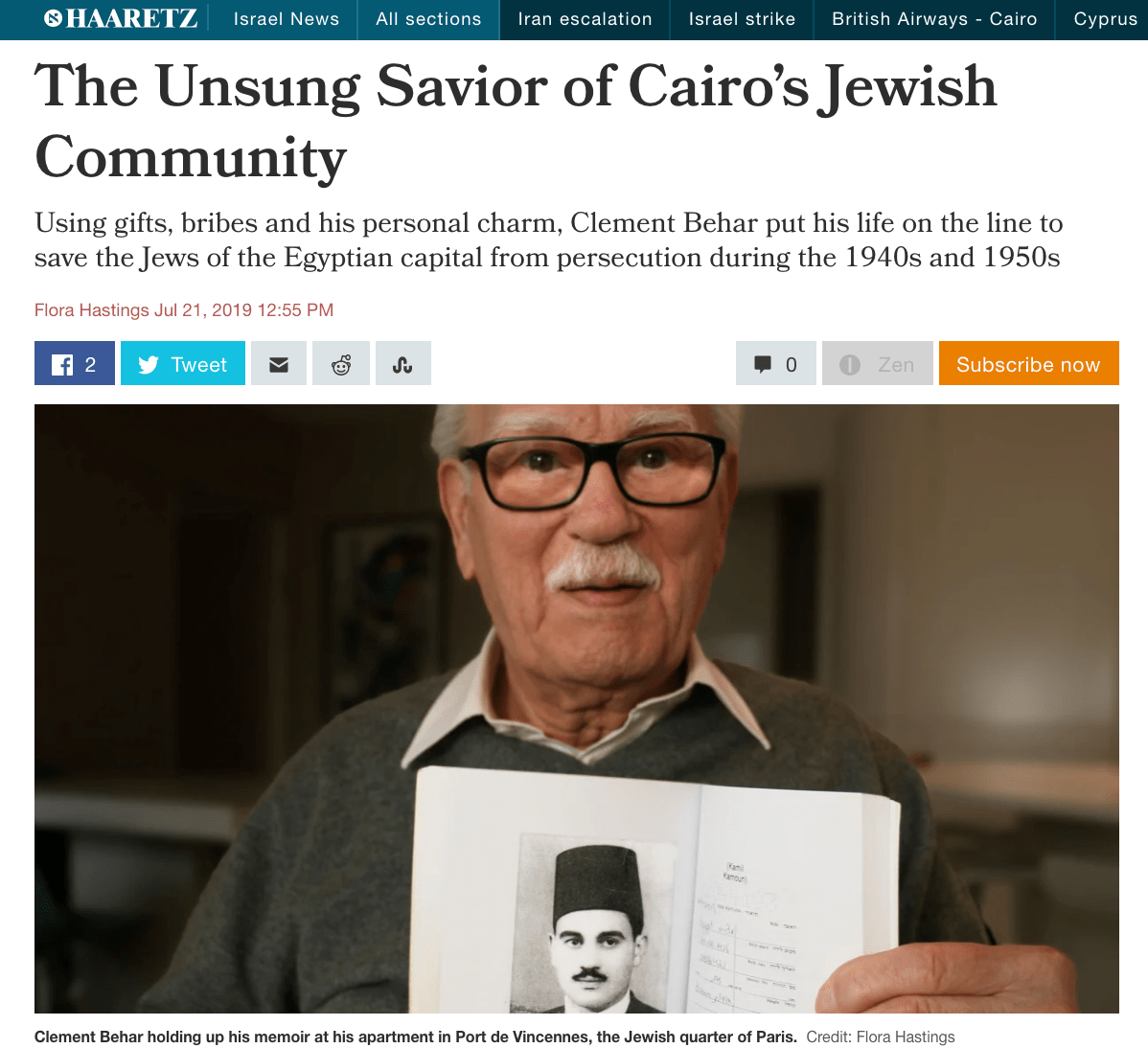

At first glance, the 92-year-old man sitting in a Parisian apartment and clutching a book to his chest does not look in the least bit like the hero at the center of a tale of a high-stakes escape.

However, this is exactly who Clement Behar was: The unsung savior of Cairo’s Jews, who risked his own life to rescue members of the community from persecution in the 1940s and 1950s.

Forty-six years later, his story is still emerging from obscurity – Behar, formerly known as Chehata, has published a memoir in which he revealed how he helped release scores of Jews from Cairo’s prisons. The self-published oeuvre, titled “A Story of a Life with a Difference,” came out in 2003.

Born in 1925, Behar grew up in the Egyptian capital at a time when the city was a Jewish, Muslim and Christian cosmopolis. Joining his father’s prospering electrical business at 15, he was propelled to Egypt’s elite social circles. As a teen, he saw anti-colonial movements gain more traction shortly after the British Empire granted nominal independence to his homeland in 1922.

His family, much like many other Egyptian Jews, enjoyed financial and social success. But in 1948 matters took a turn for the worse: Israel was established as an independent state after Jewish militants defeated the British Mandate of Palestine. A day later, on May 15, the War of Independence broke out. The young country survived the invasion of five Arab nations which opposed Jews taking over Arab lands. It even gained control over more territories, sparking a deep anti-Jewish sentiment in the region.

At the time, Egypt was home to 80,000 Jews who resided there for three millennia, with some immigrating from Europe since the late 19th century. Despite their stature, the country’s Jews were put in a precarious position over their alleged loyalty to Israel. Many of them perceived themselves as more Egyptian than Jewish, and rejected calls by Egypt’s growing ethnonationalist circle to leave.

The calls quickly escalated into violence. One infamous incident is the Balfour Day riots, which took place in November 1945. They began as anti-Jewish demonstrations on the 28th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, but quickly turned into altercations in which five Egyptian Jews were killed and hundreds were injured. In 1948, the riots worsened. Hundreds were murdered, Jewish synagogues were burned down and Jewish areas in the country were bombed. Many Jews were jailed, often on suspicion that they had spied for Israel.

This is when Behar’s operation was set in motion. “Every day, officers arrested young Jewish people, and their families came to see me and enlist my help,” he wrote in his memoir.

‘Obliged to help the Jews’

In 1953 the Egpytian Republic was born, and gave rise to a national socialist president – Gamal Abdel Nasser. Egypt was finally freed from the British occupation, but the Jewish community only suffered from these developments. The Pan-Arabist movement continued to grow under Nasser, and Jews were seen as an obstacle to its goal: Uniting all Arab nations into a single state. By 1950, 40 percent of Egyptian Jews fled. “I felt morally obliged to help the Jews,” Behar told Haaretz.

He began to do so, using his close friendship with a high-ranking police officer named El Hamichari. Behar negotiated the release of imprisoned Jews through “gifts and bribes.” Dressed neatly and wearing a traditional fez, the young Behar easily entered and left Cairo’s police stations, where he was often mistaken for an officer thanks to his command of Egyptian Arabic.

The Jewish community continued to shrink. 14,000 Jews had escaped to Israel, while others sought refuge in different countries. Egypt’s chief rabbi also became a target. In his memoir, Behar wrote that in 1954 President Nasser sent Rabbi Nahoum Effendi a “poisoned invitation.”

To mobilize anti-Israel sentiment, Effendi was called on to give a speech publicly denouncing the Jewish state. The rabbi “prayed that he would be spared the ordeal,” Behar wrote, but was powerless to decline the invitation.

Behar decided to save the rabbi. He enlisted the help of a daring Jewish hospital manager, Dr. Bensimmon, who prescribed medication for the rabbi as well as “a very strict diet which made him actually unwell.” The national papers reported that Effendi was very ill and could not attend the event. Behar wrote about the chief rabbi’s gratitude. “May God keep you near me to have you by my side in difficult times,” he told Behar.

The prison escape

Behar continued his operations to aid the Jewish community in its plight, but eventually his luck ran out. Egyptian police caught him smuggling money out of the country for the chief rabbi’s son. As he waited for his trial, Behar wrote a letter to his wife Dorette and their four children. He begged them to flee Egypt immediately. After he was sentenced to six years of hard labor behind bars, Behar “decided to escape there and then.”

In his memoir, Behar wrote that he wore civilian clothing prior to his trial. Exploiting his attire and the prison’s shortage of guards, he made his big escape. “I went downstairs, I walked to the prison gates and just walked out of prison,” he recollected.

From there, Behar bolted to a Christian monastery where he sought cover with the help of a monk he befriended when the latter paid visits to the prison. Behar wrote that for 18 months he was on the run. “I shaved my moustache. I work dark glasses and started running in all directions, incognito, to find a way of escape. I would return to the monastery at night,” he wrote.

After close to two years at large, Behar acquired a false Lebanese identity card under the name Sami Refaat Abdul Hadi. His cover story was that he was Muslim businessman. “I knew Arabic perfectly well. No one would have suspected that I was Jewish,” Behar wrote. Later, he was aided by a high-ranking police officer named Captain Said Nached, who sheltered him in his home until he was finally able to board a flight to Damascus.

Longing for Egypt

In 1956, Behar moved on from Syria to Lebanon. He was able to seek shelter there because Beirut and Cairo were political enemies at the time – then-Lebanese President Camille Chamoun, a Christian Maronite, was seriously opposed to Nasser’s Pan Arabism.

As a political refugee, Behar resided in the magisterial mansion of the president’s secretary for several months. He also managed to obtain a Lebanese passport. “After being sheltered in a monastery, I was familiar with all the prayers and Christian traditions. I was very much in need of that in the circle I was mixing in at that time,” he related in the memoir.

Later, Baher was able to secure a visa from Switzerland and made his way to France, where his wife and sons were living. In 1958 he arrived in a northern suburb of Paris as an illegal refugee, where at long last he reunited with his family. “‘They are all here! In the twinkling of an eye, I had forgotten everything: Jail, my walkabout, my nightmares.”

Speaking to Haaretz decades after his fugitive journey ended, Behar teared up when he talked about Egypt. Asked how he felt about his exile from his native land, Behar responded: “I spent at least 25 years locked up inside myself because of leaving Egypt, my roots and identity. It took me that long to accept that I live in Europe.” Despite the many years he spent in France, Behar said that he still felt more “Egyptian and Arab than Jewish.”

Six months after our interview, Behar passed away in October 2017. He did not hear of Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah al-Sissi’s surprising recent overture in which he offered to build synagogues in Egypt should members of the Jewish community choose to return. Behar himself only went back to Egypt once in 1980. In his memoir he wrote of a walk along Cairo’s Jewish quarter, where he found “the synagogue which had fallen to pieces… All I had was a blow to the heart.” He told Haaretz that his feeling was that he “returned as a tourist.”

Writing the memoir helped Behar accept his journey, but he remained ambivalent about his homeland until his death. His is a tale of triumph; it is also a story of bitterness and longing, which linger with may other Jews who were forced to flee their Middle Eastern homes a century ago.

The New Spanish Islamophobia

Posted on April 26, 2019

Published by The New Internationalist

Tanned, muscular men ride stallions across a rural landscape. Plaintive piano plays in the background. Where are these men? The title of Vox’s political campaign video tells you: ‘The Reconquista will begin in the lands of Andalusia’.

This controversial slogan is part of a strategy that helped secure the rising far-right party twelve seats in Andalusia’s regional election last year. Next week, Vox are one of five main contenders in Spain’s general elections, signalling the party’s unanticipated growth. It is expected to receive 29-37 per cent of the vote.

The Reconquista, meaning the ‘reconquering’, draws on the history of the Iberian Christian conquest of Muslim Spain, which ended in 1492. Vox’s proposed political reforms make the relevance of this history clear: if elected, the party claims it will deliver an end to supposed uncurbed migration, placate the ‘threat’ to Spain’s national identity from the growth of Islam, end state-funded abortion and repeal gay marriage laws.

Spectres of the past

The history of medieval Christian-Muslim conflict forms this far-right party’s repertoire of symbolism. For eight centuries, Spain was governed by Islamic rulers, known as the Moors. In 711 CE, the governing Umayyad dynasty travelled from Syria to Spain and eventually conquered the then Visigothic lands, renaming them ‘al-Andalus’. Contemporary Spain is replete with vestiges of this past, from Moorish architecture to the many Arabic-origin words in the Spanish language.

With the end of the Reconquista in 1492, a Spanish national identity began to emerge. The newly reigning Catholic monarchs took violent measures to forge it. Those who were not Catholic would not be considered Spanish in this new social order. This process would eventually lead to the expulsion of the peninsula’s vast Jewish and Muslim populations.

Spanish ethno-nationalism continued well into the 20th century. Spain’s former dictator, General Franco, granted the Catholic Church immense power, prohibited any religion save Catholicism and enforced the standardisation of ‘core’ Spanish culture, from the Castilian language to bullfighting. Francoist Spanish nationalism was defined against the nation’s former Jewish and Muslim subjects, such as through the dictator’s heavy use of Spanish Reconquista symbolism in his propaganda. Francoist rhetoric even blended the myth of the ever-present ‘Moorish threat’ to Spain with the ‘menace’ of Eastern European communism.

With the death of Franco in 1975, Spain officially disbanded its explicitly authoritarian structure. However, its ethno-nationalist past still haunts the public sphere.

‘Spanishness’

Moroccans are Spain’s second largest minority. Many within Spain’s Moroccan community are ancestrally related to Spain’s historic Muslim population. At a market in Cordoba, pejoratively called ‘Morro’s Mercado’ by locals, Tariq, a Moroccan vendor tells me about the strong anti-Muslim prejudice he recognises in Andalusia: ‘They think in Morocco there are only camels and the desert,’ he says. Beyond the perception of Morocco as an excessively ‘backwards’ country, some Spaniards even perceive the influx of Moroccan immigrants to Spain since the 1970s as posing a ‘re-Islamization’ of the country.

Outside more blatantly Islamophobic cases, there are Spanish traditions which revisit this Christian-Muslim schism. Each year on 2 January, individuals across Spain dress as either ‘Moros’ or ‘Christianos’ and re-enact the last battle of the Reconquista, where the medieval stereotypes of the Moors as violent and religiously fanatic are inflated through carnivalesque caricatures.

Although these cultural rituals are thought to commemorate a strife from a by-gone past, Vox’s dogwhistle calls for a new Reconquista casts these cultural rituals in an even darker light, further entrenching the idea of Muslims as antithetical to ‘Spanishness’.

Acceptable in the mainstream

Appeals to the Reconquista are not a new development in Spanish politics. In an attempt to drum up support for the Iraq War, José Aznar, Spain’s former Conservative prime minister, explicitly linked the medieval Moors to al-Qaeda. He stated in 2004 that ‘the problem of Spain with al-Qaeda began with the invasion of the Moors’, who were repelled thanks to the ‘successful Reconquista’.

Vox is building on this rhetoric. The party’s leader, Santiago Abascal, petitioned for Andalusia’s regional day to celebrate the conclusion of the Reconquista in 1492. At a meeting in Seville, Abascal stated that he wanted the ‘Andalusia of the Catholic Monarchs against that of Blas Infante’. Infante was a libertarian socialist writer known as the father of Andalusian nationalism. In the early 20th century, he strived to turn Spain’s legacy of medieval Jewish, Muslim and Christian co-existence into a contemporary reality.

The language used in the party’s political speeches is rife with Islamophobia. Vox’s secretary general, Javier Ortega Smith, stated in 2016 that ‘the enemy of Europe is called the Islamist invasion’. Santiago Abascal, Vox’s leader, rejoined Smith by stating that Spain’s Muslim community will become a ‘problem’ in an interview last year. The party’s proposed political reforms include banning both Islamic education and halal food in Spanish state schools.

This is all part of a Europe-wide phenomenon. In the week following the New Zealand/Aotearoa mosque shootings on 15 March, the number of anti-Muslim hate crimes reported across Britain increased by 593 per cent. These attacked are fuelled by continent-wide stereotypes, from the perception of Muslims as jihadists to perceiving Muslim immigrants as an unassailable threat to Western values.

Vox’s anti-Muslim stance have helped win the party favour with Europe’s largest far-right political groups. In 2017, Abascal claimed an affinity with France’s ultra-conservative Marine Le Pen for their mutual protection of ‘Christian Europe’. Le Pen, along with the Netherland’s far-right Geert Wilders, have openly supported Vox through expressing hopes that the party will gain seats in May’s European parliamentary elections. The growing coordination between Europe’s far-right parties only threatens to strengthen the institutional legs of a continent-wide Islamophobia.

Jewish history caught in independence tug-of-war

Posted on January 11, 2018

Published for Jewish Renaissance Journal

After a 400-year vacuum, Judaism has reappeared on the Iberian Peninsula in unexpected ways. Spanish institutions have proudly united medieval Sephardi identity with a modern Spanish identity. Meanwhile, Catalan institutions recently asserted that their medieval Jewish communities had a separate Catalan identity.

In the 1990s the Spanish government revived an interest in Sephardi history and formed La Red de Juderias, a multi-million-euro Jewish tourism network. Spain’s Jewish archaeological sites were renovated and archives digitised to rediscover this unknown legacy. ‘Spanish’ and ‘Sephardi’ became interchangeable terms in the Red’s publications.

The pluralism of the medieval La Convivencia – an era of intellectual symbiosis between Muslims, Jews and Christians – was reimagined as being the foundation of Spain’s current progressive identity. The act of connecting modern Spain with the past was a precursor to the 2015 Law of Return for Sephardi Jews. The introduction of the law can be seen as an attempt to diversify Spain’s national image.

But which Spain? Medieval Spain was built by Jews, Muslims and Christians who coexisted under La Convivencia. The Catholic, Castilian Spain that followed, whose foundations support today’s nation, has little to do with this history. The Law of Return requires proof of the applicant’s ‘special connection’ to Spain through a Spanish language and culture test. Most Right of Return laws, such as those of Germany or Poland, do not require this.

Alfons Aragoneses, head of law at Barcelona’s Pompeu Fabra University, questions the historical accuracy of Spain’s identification with Sephardi Jews: “Spain did not exist before 1492, but the law supposes that the Sephardim were conscious of belonging to Spain and that they were always nostalgic for Spain. Spain did not exist until the 19th century!” At least, the Spain that formed after the 1492 union of the Castilian and Aragonese Crown did not exist when the Sephardim lived on the Peninsula.

Catalonia too has been weaving nationalistic threads into its Jewish past. Tessa Calders, the daughter of the renowned Republican exile Pere Calders, has been calling for the current interpretation of Jewish medieval history to be revised and the adapted version to be recognised in any representation of Jewish history. “The Jews were kicked out of Spain and lost memory of their Catalan identity. Now Spain has reinvented their past,” says Calders, who is a lecturer in Hebrew at the University of Barcelona. She believes the Jews living in northern Spain before the expulsion were not Sephardi but were Catalonian.

This pro-Catalan understanding of history has been embraced by Catalonia’s regional governments: in 2016, five municipalities split from the Red de Juderias to create a new tourism network, the Xarxa de Calls. Jusep Boya is the head of Museums for Catalonia and the manager of this new organisation. In his office off Barcelona’s Las Ramblas, he envisaged the new network as a vehicle for Catalonia’s reconnection with its Jewish history. “We cannot comprehend Catalonia without the Jewish culture which is attached to the very soul of Catalonia,” he said.

Pancracio Celdrán, a former professor of medieval history at Haifa University, disputes that there was a conscious 15th-century Catalan identity. “These medieval ‘Catalan Jewries’ were really the Jews of the Kingdom of Aragon, not of Catalonia.” Others say that Catalonian nationhood only developed in the 19th century.

With only 40,000 Jews in Spain today, the groups who should have a platform to challenge these revisions of history have no representational power. Most of those involved in the departments for Jewish tourism in both governments are not Jewish and have little specialisation in the history of Jews living in Spain. The situation needs addressing: Spain was ranked the third most antisemitic country in Europe in a 2014 survey. Instead of politicising Sephardi identity for their own narratives, isn’t it time for both sides to let the Sephardim delineate their own ancestral past?